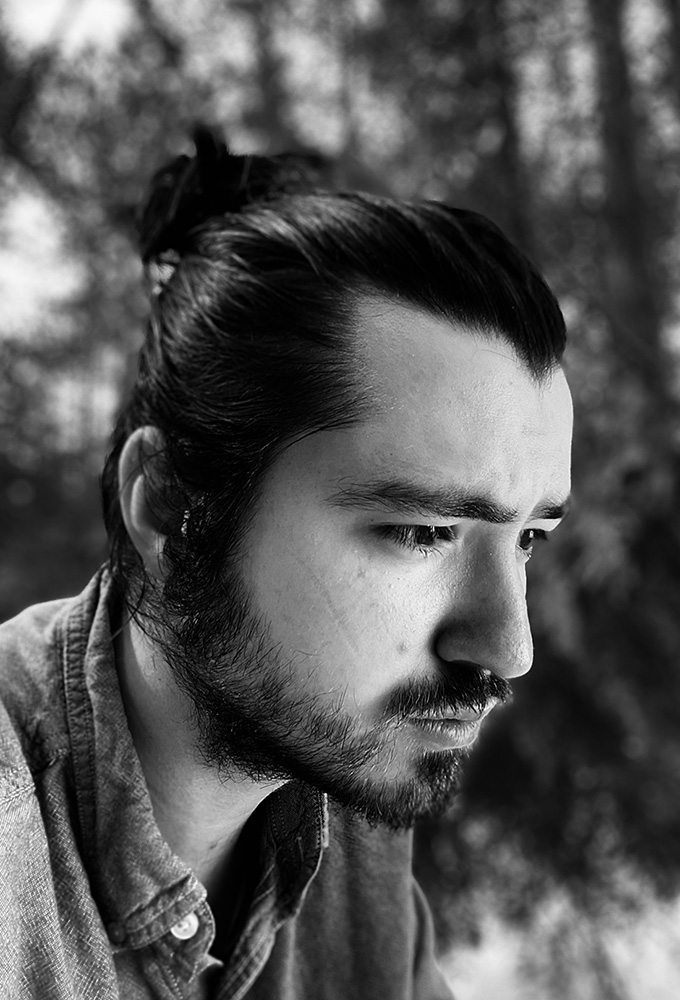

Ben Anthony

Digital Cinema

-

Artist Statementarrow_drop_down

Having spent my whole life in the small town of Marquette, Michigan, it is often easy to feel isolated from the rest of the world. Through cinema, I found a means to transport myself to places that lay beyond the borders of my experience: from the poverty-stricken streets of 1950s Italy, to war-torn Poland, to the Edo Period of Japan. Time and time again I witness the power of film as it exposes me to new ideas, perspectives, philosophies, and ideologies; it is a passport inviting newcomers to experience unfamiliar and diverse cultures and customs all filmmakers have unconsciously captured in their works.

Gazing was designed as an exploration of the relationship between cinema and poetry. Unwittingly, I had stumbled onto the same discovery filmmaker, theorist, and poet Andrei Tarkovsky had made and published in his book Sculpting in Time (1984): the haiku is the art form spiritually and structurally closest to Cinema.

Consider:

The old pond

a frog leaps in.

Sound of the water.

- Bashō

This example activates both visual and auditory imagery in the brain. With concision, Matsuo Bashō paints a powerful and vivid image with sharp clarity. A reader can easily imagine the stillness of the water disturbed by the frog, followed by a splash, and then a return to silence. This experience is created through a deliberately paced assembly of images, not dissimilar to the editing of Films; in the construction of montage comes new meaning.

The short film, Gazing was largely inspired by the old Japanese haikus of the feudal era. Though not directly based on the traditional poems, they heavily inspired the poem written to serve as the shooting script. Like many of my films, it is heavily influenced by the theories of “slow cinema” laid out by Paul Schrader in his book Transcendental Cinema and Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time. This is reflected in the minimalist plot, slow/lack of camera movement, and long shots. The lengthy shot duration is meant to create a meditative experience, a means of reflecting on life and death, as the former (life) leaves a man in the woods.

Gazing is ultimately a tribute to the power of universal, human cinema, and a celebration of the haiku: the original moving image.